Jackson Ayres, writing for the Los Angeles Review of Books, explores the notion – one which I think has become basically commonsensical – that mainstream comics went through a "Dark Age" in the 1980s and 1990s characterized by increased violence and "edgy" interpretations of existing characters. This is typically understood as an effect of the "quality popular graphic novels" produced by Alan Moore and other "British Invasion" creators, which we discuss in chapter 5 of our book. Much as everyone is focusing on Deadpool's R-rating right now, many creators imitated the surface features of works like Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns. There's a lot of unpack in this essay, which drew my attention not only for discussing the "Ages" model of comics history (one of my longtime pet peeves) but also for writing about ’90s Aquaman in the LA Review of Books, but what I found most interesting was the way that Ayres understands the "grim and gritty" aesthetic as the flip side of camp. Indeed, he notes that the first use of that particular phrase in connection with superheroes was in an episode of the 1960s Batman TV series.

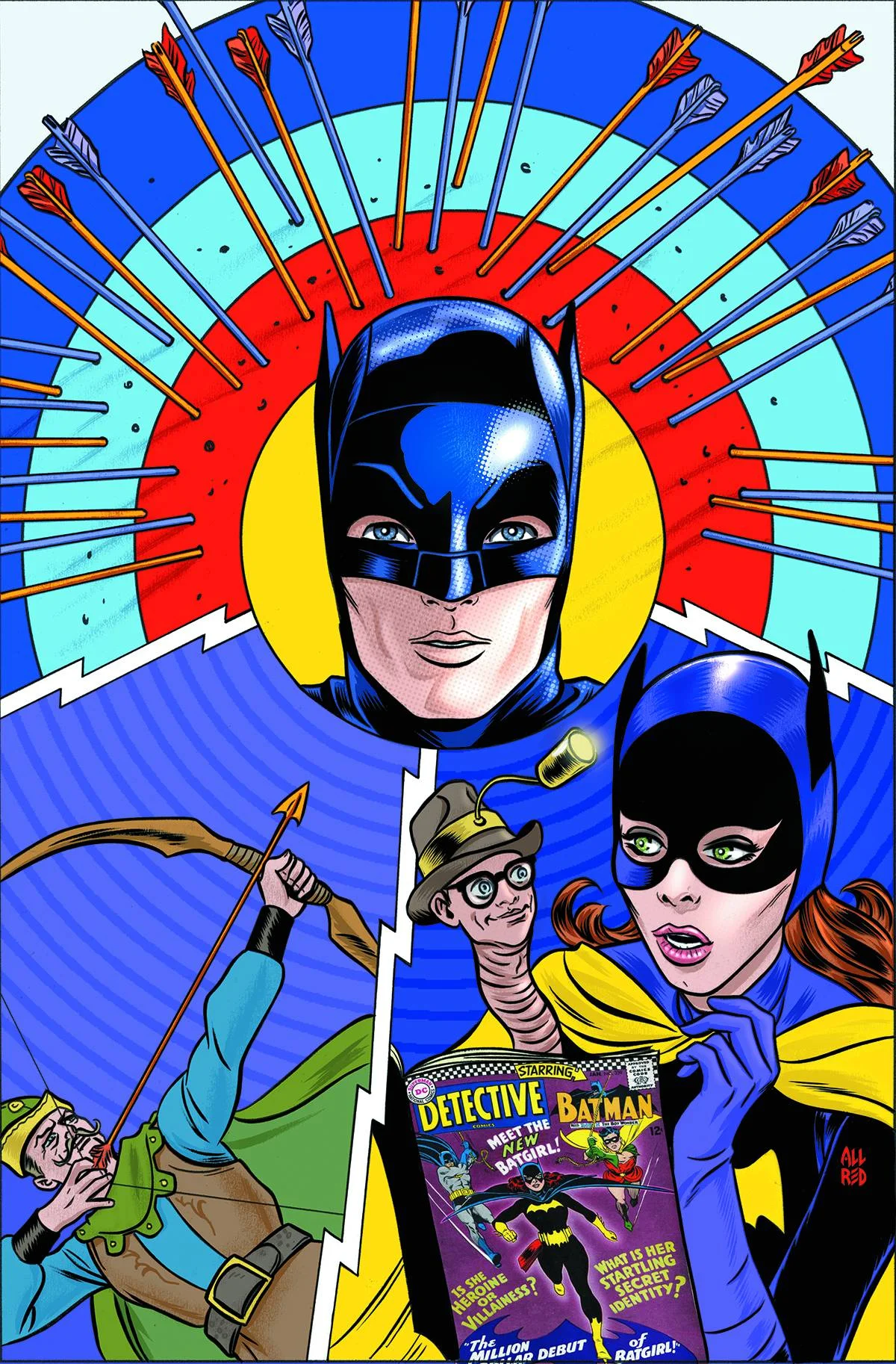

Cover artwork to Batman ’66 #18 by Mike Allred and Laura Allred. © 2014 DC Comics.

The Batman series is an interesting case. Its campiness hung like an albatross around the superhero genre's neck for many years, but Ayres suggests it has undergone a critical renaissance recently, a transformation of consensus marked by the inclusion of the Adam West Batman costume (though not the Adam West Batman body!) in the Arkham Origins video game, DC's Batman '66 ongoing series (initially a digital-only title upgraded by popular demand to print, as well) with gloriously poppy covers by Mike and Laura Allred, and a ’60s style Joker figurine from Funko's Pop Vinyls series, complete with Caesar Romero's painted-over moustache:

The revival of camp might be seen as marking the decline of grim and gritty, but it in fact underscores the intimate relationship between the two, the covert similarities linking them. The skepticism about superheroes and heroism associated with grim and gritty, for example, was already present in the campy Batman…. While the temporal distance separating contemporary comic book fans from the show allows a comfortable pleasure in its humor, make no mistake: it is underwritten by a deep and abiding disdain for its source material.

Both camp and grim and gritty, moreover, serve to displace such disdain by discovering new ways to invest cultural capital into a genre associated with crudeness and puerility.

How do camp and the "grim and gritty" aesthetic, each in their own way, make this "displacing" move? In Artworld Prestige: Arguing Cultural Value, Timothy Van Laar and Leonard Diepeveen (2013) suggest that one of the key anchors for the regime of value that dominates contemporary art is the quality they call "aboutness." That is, the artwork isn't simply what it appears to be but is a knowing, informed exploration about what it appears to be:

To be a serious painter, you can't just 'infuse,' you have to be about infusion. In a given artwork, if the aboutness is directed at art in general, then it is theory—as is irony if it addresses the artworld, and meta-reflection if it is about art practice. The consequences for prestige are obvious: in the artworld, meta-reflection, 'aboutness,' generated prestige. (47)

That is to say, aboutness involves stepping back or distancing oneself from the object under contemplation. The reader of Bourdieu's sociological studies of cultural production and taste will recognize this as an expression of the "aesthetic disposition" that marks elite tastes: the preference for intellectual pleasures over sensuous ones, for engagement with form rather than function.

From "What's So Funny About Truth, Justice, and the American Way?" by Joe Kelly, Doug Mahnke, and Lee Bermejo. Action Comics #775. © 2001 DC Comics.

The seemingly radically opposed strategies of camp and "grim and gritty" relied on the same underlying principle: evading the conventional judgement of superheroes and comics books and childish by putting them in aesthetic scare quotes. Both assume that the reader knows the original source material being adapted or re-interpreted is silly, and so both insert distance between the reader and the object – in the one case, using irony and in the other heavy helpings of "seriousness." As a result, the background "condition of possibility" for most of the comics discussed by Ayres as tracking the shifting sensibilities of superhero readers – from Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns to Kingdom Come and "What's So Funny About Truth, Justice, and the American Way?" – is that they are fundamentally about (or, at least, were marketed as and susceptible to being interpreted as about) superhero comics themselves and about the changing demands made on them by their audiences.